From Packard to Technify: The Ups & Downs Of Diesel Engines in Aviation

On February 17, 1897, Rudolf Diesel revolutionized the internal combustion engine when Moritz Schröter demonstrated the first viable diesel engine, the Motor 250/400, to engineers and industrialists. Despite initial design and fuel-injector issues, resolved by Burmeister & Wain, the engine's practicality was demonstrated, leading to broader adoption beyond the industry. The first diesel ships appeared in 1903, the ocean-going MS Selandia in 1912, and the first diesel truck in 1908.

But, how have diesel engines impacted the aircraft industry? There have been ebbs and flows when it comes to aerial diesels, as manufacturers attempted to adapt this new technology to the equally new technology of aerial flight, but consistently ran into roadblocks that impeded any widespread adoption; this comes primarily from a combination of cost, technological bottlenecks, and better contemporary alternatives. However, since the early 1990s diesel engines for aircraft have seen a new lease on life thanks to those same factors facing the diesel engine's compeititors in the field of aviation.

The Packard DR-980: The First Aviation Diesel

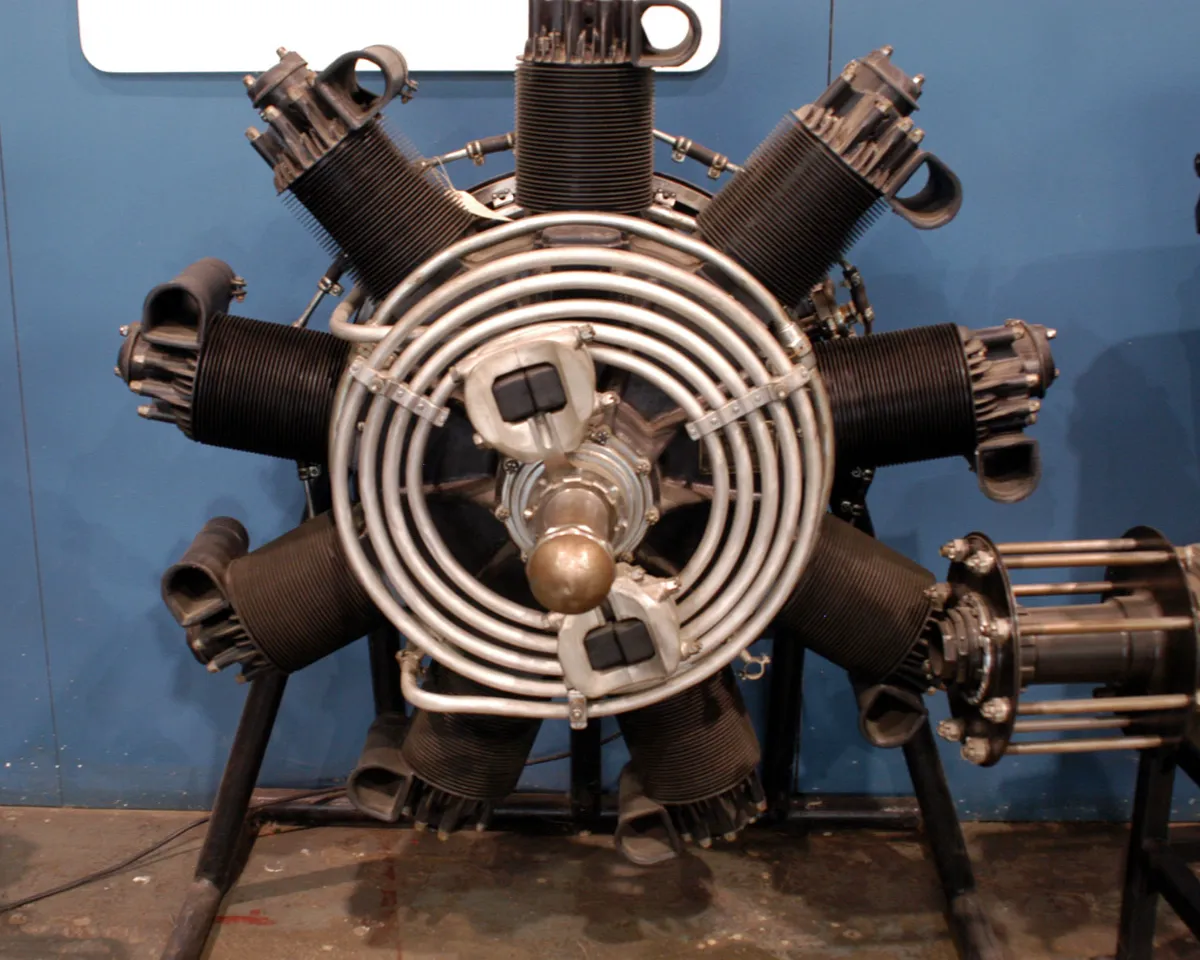

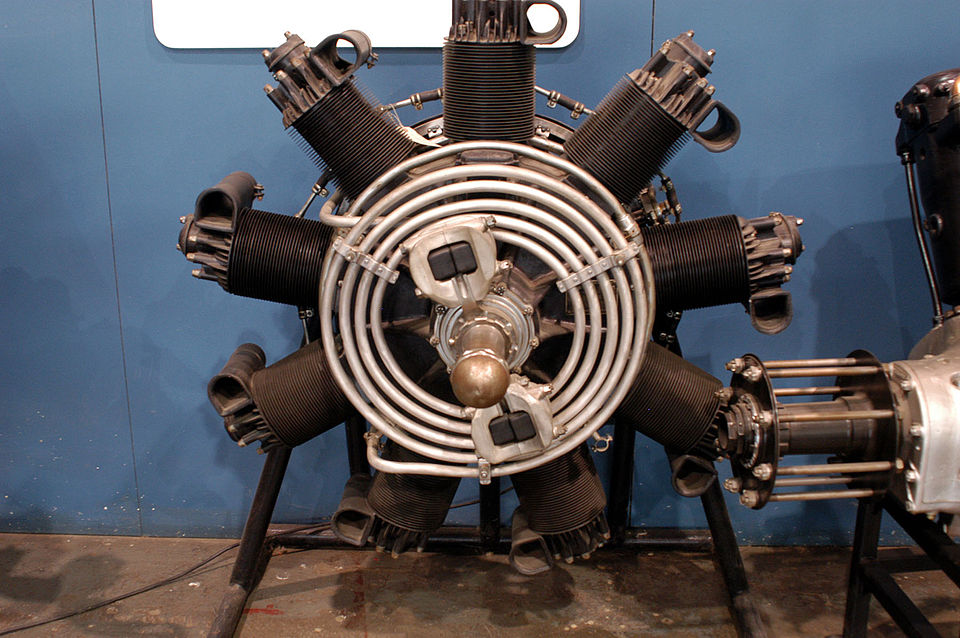

The Packard DR-980 was the first successful diesel engine built for aviation, a collaboration between Packard Motor Car Company and German engineer Hermann Dorner (1882–1963). Dorner, a key figure in German aviation, was chief designer for Deutsche Flugzeug-Werke and Hannoversche Waggonfabrik during WWI, creating combat aircraft and patenting diesel-engine innovations. Although a diesel engine—the Beardmore Torpedo—was used in aviation from 1927 (installed in the R101 airship), it was too large and inefficient for smaller applications.

Origins & Development

The DR-980 originated from a 1927 licensing deal between Packard’s president, Alvan Macauley, and Dorner. Packard’s chief aeronautical engineer, Captain Lionel Woolson, proved Dorner’s 'solid’ fuel injector by testing air-cooled and water-cooled diesels. Woolson and Dorner then developed the engine with help from Packard engineers and Dorner’s assistant, Adolph Widmann. Woolson focused on weight reduction, while Dorner designed the combustion system.

Woolson and Dorner’s contributions are crucial. The diesel aircraft engines available at that time lacked a sufficient power-to-weight ratio for effective, affordable flight, making them unattractive to both the rapidly expanding airlines of the day and potential military customers. Dorner’s patented solid injection system replaced the reservoir and compressor in Diesel’s original design. Rather than needing high-pressure air reservoirs and compressors, it relied on the combustion chamber’s shape and pistons for airflow. Dorner also added individual pumps to each injector, removing the need for high-pressure fuel lines.

Woolson and Packard’s engineers improved magnesium-alloy castings, replacing aluminum castings in other engines. They lightened the crankshaft by flexibly mounting counterweights and used a single overhead valve in the cylinder head to reduce the number of parts and weight. Later DR-980 versions featured an oil cooler around the propeller shaft.

Specifications

- Type: 9-Cylinder Diesel Radial

- Bore: 4 13/16 in (122.2 mm)

- Stroke: 6 in (152.4 mm)

- Displacement: 980 in3 (16 L)

- Dry Weight: 550 lb (227 kg)

- Valve Train: One valve per cylinder, overhead valve

- Cooling System: Air-cooled

- Power Output: 240 hp (179kW) at 2,000 rpm

- Specific Power: 0.25 hp/in3 (11.2 kW/L)

- Power-to-Weight Ratio: 0.44 hp/lb (0.8 kW/kg)

Testing, Production, & Failure

The engine’s first test flight occurred just a year later on September 19, 1928, at Packard’s proving grounds, flying a Stimson SM-1DX “Detroiter” with Woolson and Packard’s chief test pilot, Walter E. Lees, aboard. This successful test prompted Packard to invest $650,000 (equivalent to $12,346,198.83 in 2025) in a manufacturing plant dedicated solely to the DR-980. By July 1929, the goal was to produce 500 engines each month.

The engine’s first cross-country flight was on May 13, 1929, with the same plane and crew flying from Detroit, MI, to Norfolk, VA. It lasted 6 ½ hours and cost $4.68 in fuel, equivalent to $88.89 in 2025 dollars, much less than a comparable gasoline engine would have used, which would have used five times as much fuel. A second flight was scheduled for March 9, 1930, from Detroit to Miami. Following minor improvements, the engine received the first-ever type certificate from the Department of Commerce on March 6, 1930, after extensive testing. It also set a world record for a non-refueling flight of 84 hours and 33 minutes over Jacksonville, FL, from May 25 to 28, 1931.

The DR-980 was later licensed and produced by major companies like Rolls-Royce, Panhard, Junkers, Fiat, and Guiberson. Despite its impressive record and pioneering features—such as a dynamically balanced crankshaft and magnesium-alloy castings—the engine ultimately proved to be a failure. Production stopped after Woolson's death in an April 1930 accident (Dorner returned to Germany the next year), and the engine's significant vibrations and diesel fumes made it unpleasant for passengers in the airliners that used it. Additionally, the engine was never produced in sufficient quantities to compete effectively with similar gasoline engines.

Diesels Across The Pond: European Diesel Developments in The Interwar & War Periods

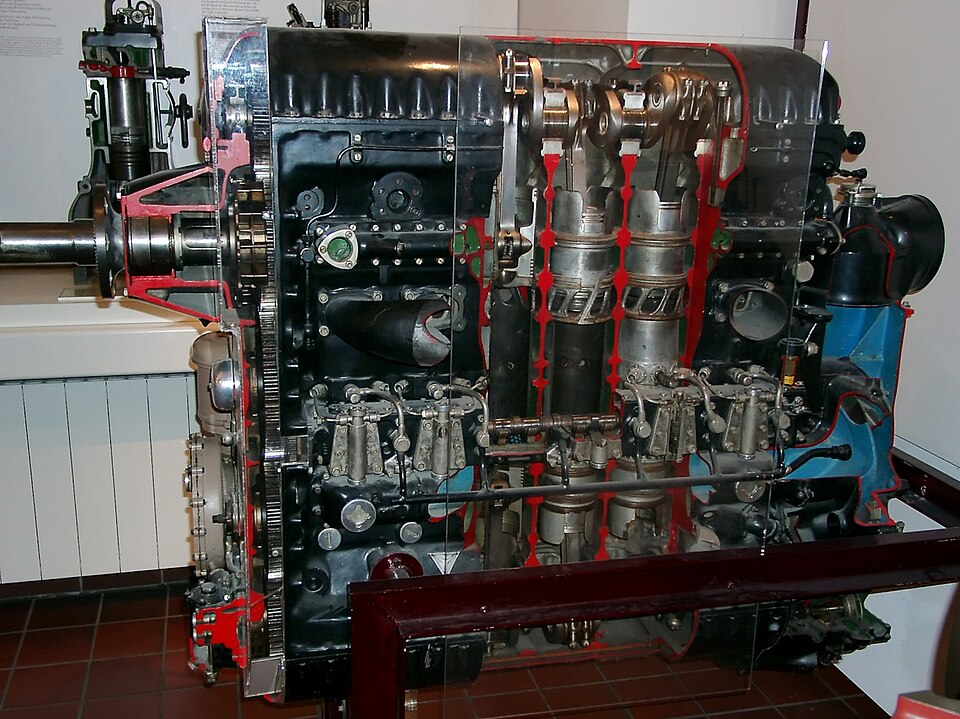

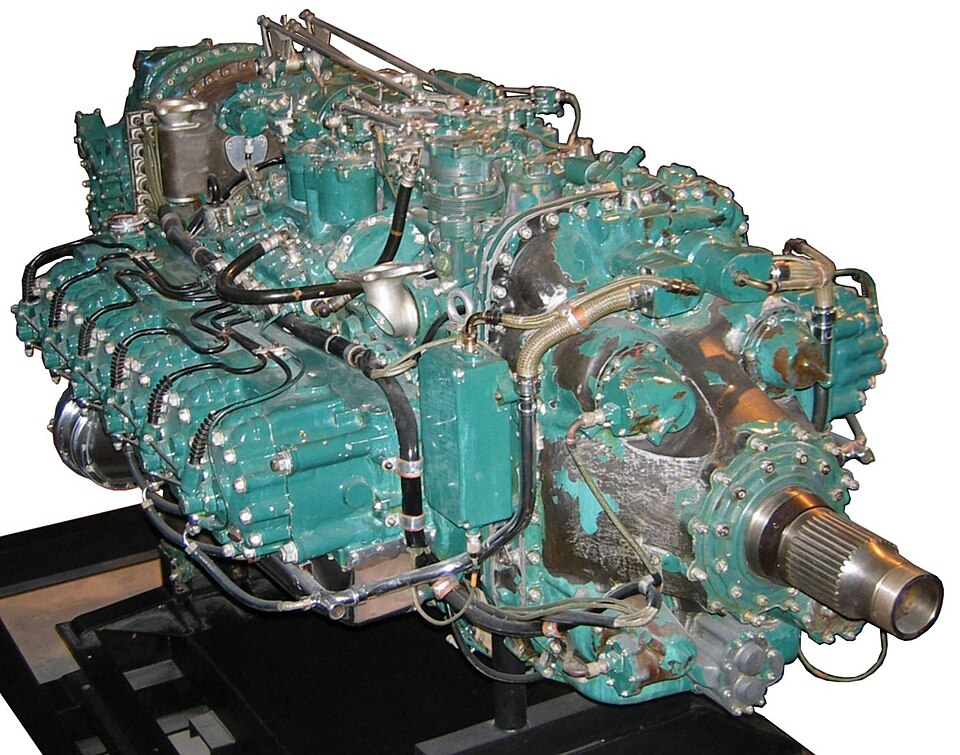

German innovation in diesel aviation engines is notable, with some of the most successful being German. The Junkers company, founded by Dr. Hugo Junkers in 1895, started experimenting with diesel engines in 1911. These efforts led to the Junkers Mo3 of 1913, a four-cylinder opposed-piston engine. Issues with the Mo3 prompted the development of the Fo3 in 1924, a vertical five-cylinder engine. The Fo4, a six-cylinder testbed, was tested in 1928, including a test in a Junkers G.24 in August 1929.

After extensive testing, Junkers succeeded with the refined Jumo 4, which was redesignated as the Jumo 204 by Nazi Germany’s Reichsluftfahrtministerium (Ministry of Aviation). Although the Jumo 204 had limited success, it inspired Napier’s 1947 Deltic engine, designed for naval and railway use. An adaptation of the Napier-Culverin (a licensed Jumo 204), it was among the most powerful and compact diesel engines of its time.

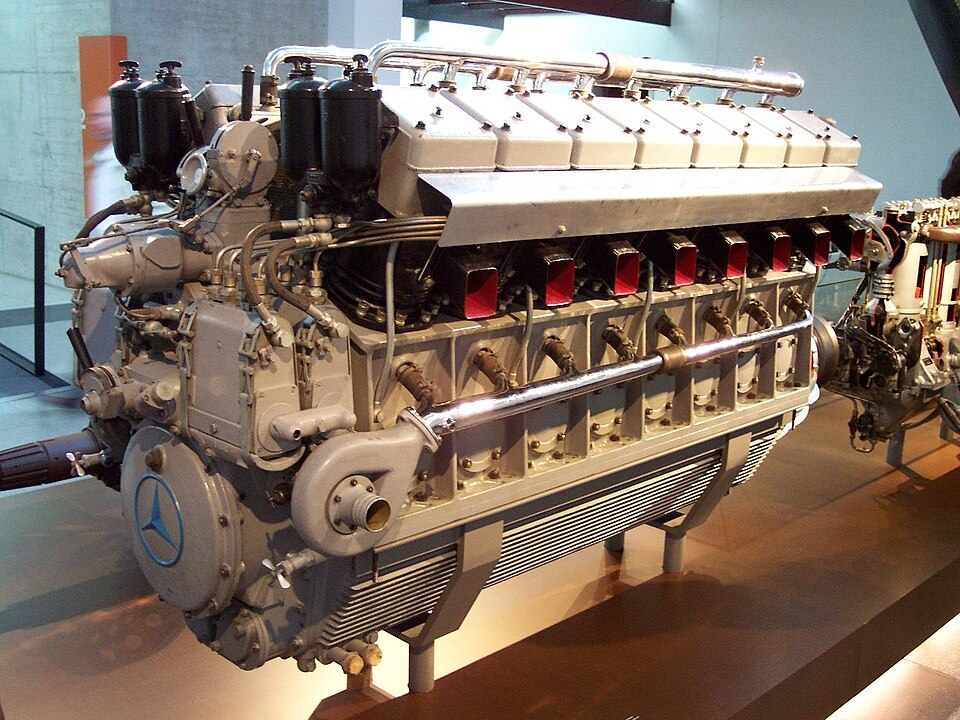

The Jumo 205 was the most extensively produced engine in the Jumo series, powering various airships and Luftwaffe flying boats due to its fuel-efficient design. These included the main maritime patrol aircraft, the BV 138, and the largest Axis-built flying boat of World War II, the BV 222. Another German diesel engine was the Daimler-Benz DB 602, first introduced in 1933. It was similar in size and weight to the earlier Beardmore Tornado but delivered substantially higher power output. Liquid-cooled, these engines powered the iconic airships of the Hindenburg series and four Schnellboot fast-attack boats; in the latter application, the engines were designated the MB502.

French & British Diesel Testing

France and Britain experimented with their own aviation diesel engines. The French company Bloch tested a variant of their MB.200 series bombers, called the MB.203, which used radial diesel engines developed by the Service Technique de l’Aéronautique and the aeronautical engineer Pierre Clerget. Clerget's company, Clerget-Blin, had gone bankrupt in 1920. Meanwhile, in 1932, the British Air Ministry launched a program to convert the Rolls-Royce Condor's petrol engine to a compression-ignition engine. Although the engine layout largely remained the same, the engine was reinforced to handle the increased stresses of compression ignition. This increased the engine’s weight from 1,380 pounds (630 kg) to 1,504 pounds (682 kg). Although the engine was tested in a Hawker Horsley biplane to assess the potential for using diesel engines in flight, it was neither further developed nor adopted. However, it was the second diesel aviation engine to pass the 50-hour civil-type test for compression-ignition engines, after the Beardmore Tornado.

Charomskiy ACh-30 & M-40

In the Soviet Union, the main diesel aviation engines were the Charomskiy ACh-30 and M-40, with the M-40 based on the early 1930s AN-1RTK turbo-supercharged engine. Unlike the AN-1RTK, the M-40 replaced the supercharger with two E-88 turbochargers and intercoolers. It failed acceptance testing in May 1940, but production at Leningrad’s Kirov factory started; it halted in the fall of 1941 after 120 engines. The boosted M-40F was tested in summer 1940 and used in the Yermolaev Yer-2 bomber in 1941 but was not accepted. The M-40 was also considered for the KV-4 heavy tank.

The ACh-30, which shares its lineage with the M-40 from the AN-1RTK, was developed in 1939 at the Factory No. 82 laboratory near Moscow and underwent testing in early 1940. Production started in May 1940 but was delayed until 1941, during which 44 units were made as the M-30. Plans to move production to the Kharkov Tractor Factory were canceled due to the engine's poor performance, including RPM and oil-related problems at high altitudes and in cold weather. Full production ceased in the fall of 1941 when the Germans captured Factory No. 82 during the Battle of Moscow.

However, the demand for economical engines for Soviet long-range bombers led to the restart of production in June 1942 at Factory No. 500, using evacuated equipment from Factory No. 82. Supercharged versions also began development, utilizing superchargers from the Mikulin AM-38 and intercoolers from the Klimov M-105; the superchargers from the AM-38 were preferred, with this version designated as the M-30B. In addition to 34 new production M-30Bs, 35 incomplete M-30s were modified to the M-30B standard. The ACh-30B engine was officially approved in June 1943, following earlier unofficial production. Factory No. 45 also started production in late 1943. In total, 1450 ACh-30Bs were made by both factories before production ended in September 1945.

The ACh-30B served as a testbed for a motorjet, with its built-in piston engine powering the jet’s compressor. It was tested from June 1944 to May 1945, but was never installed in a production aircraft. A throttled version, the M50-T, was used in the IS-7 prototype heavy tank, and a modified M50-T, known as the M-850, was employed in the Object 277 tank prototype.

Service Use of Soviet Diesels

The ACh-30 and M-40 engines were used with the Yermolayev Yer-2, a twin-engine long-range bomber, and the Petlyakov Pe-8, a four-engine bomber. In 1941, the Yer-2 was tested with the M-40F; although it offered better fuel efficiency, the increased weight required stronger landing gear and a larger wing area. While the M-40F was still in development, testing with the ACh-30B also began. This version, called the Yer-2/ACh-30B, featured a revised cockpit and extra armament and entered production at Factory No. 39 in Irkutsk at the end of 1943. It remained in operation until the late 1940s.

In 1941, Pe-8 aircraft were fitted with either the ACh-30 or the M-40 engines due to a shortage of the original Mikulin AM-34FRN engine. Nineteen planes used these engines, and while they significantly extended their range, they were not sufficiently effective. By the end of 1941, the diesel engines were replaced. Pe-8s with M-40 engines, along with Yer-2s, were assigned to bomb Berlin via Leningrad; however, the operation failed, and several Pe-8s were lost, mainly because of the M-40's unreliability.

Specifications: ACh-30B

- Type: V-12, turbo-supercharged, four-stroke

- Bore: 180 mm (7.1 in)

- Stroke: 200 mm (7.9 in)

- Displacement: 61.04 L (3,725 in3)

- Dry Weight: 1,290 kg (2,840 lb)

- Supercharger: Geared, centrifugal type supercharger

- Turbocharger: 2 x T1-82

- Cooling System: Liquid-cooled

- Power Output: 1,500 hp (1,100 kW)

- Compression Ratio: 13.5:1

Specifications: M-40

- Type: V-12, turbocharged, four-stroke

- Bore: 180 mm (7.1 in)

- Stroke: 200 mm (7.9 in)

- Displacement: 61.04 L (3,725 in3)

- Dry Weight: 1,150 kg (2,540 lb)

- Turbocharger: 4 x E-88

- Cooling System: Liquid-cooled

- Power Output: 1,250 hp (930 kW)

- Compression Ratio: 13.5:1

Aviation Diesels In The Postwar Period: The Napier Nomad & British Diesel Efforts

After World War II, interest in diesel-powered aircraft engines dropped significantly due to the rapid rise of jet and turboprop engines in both civilian and military sectors. Jet and turboprop engines offered better power-to-weight ratios than diesel engines. This was especially important in the civilian market as the demand for larger airliners, increased capacity, and longer ranges grew.

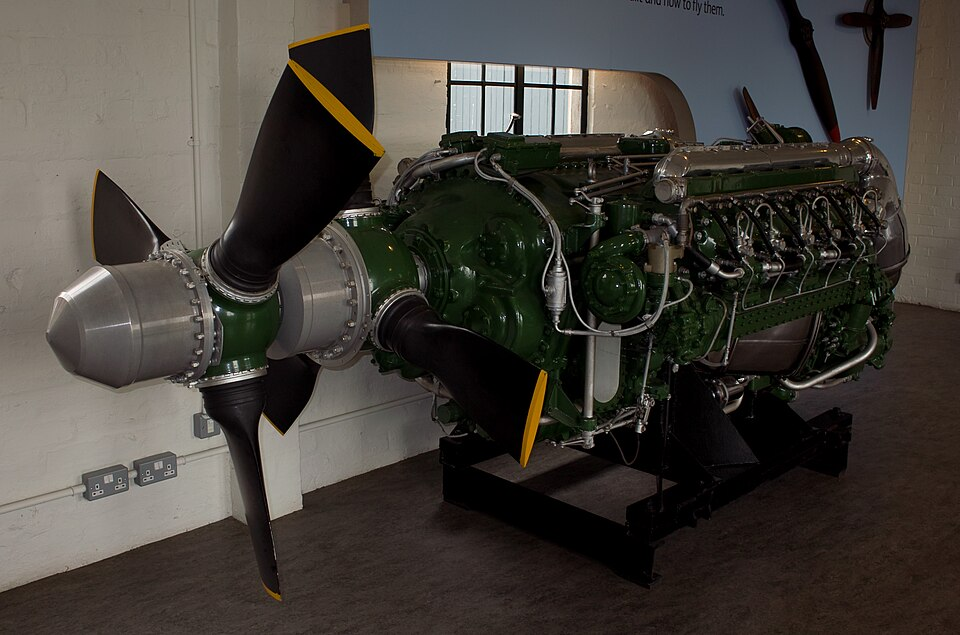

The British engineering firm Napier & Son was nearly the only one to focus heavily on general aviation diesel engine research after the war. Its previous work included the prewar Napier-Culverin, based on the Junkers Jumo 205. Since 1946, it had also been developing the Napier Deltic, a compact, high-power diesel engine derived from the Culverin, designed for marine and railway applications. Napier resumed diesel aircraft engine development in 1945 after the Air Ministry showed interest in a 6,000 hp engine with good fuel economy. It restarted Culverin development, combining two engines into a 75-liter H-block to meet this need. An H-block is a piston engine with two flat engines and separate crankshafts, each connected to a single output shaft. Similar to the wartime petrol-powered Napier Sabre, the diesel engine's size limited its market, prompting the adoption of a 12-cylinder horizontally opposed engine, the Napier Nomad.

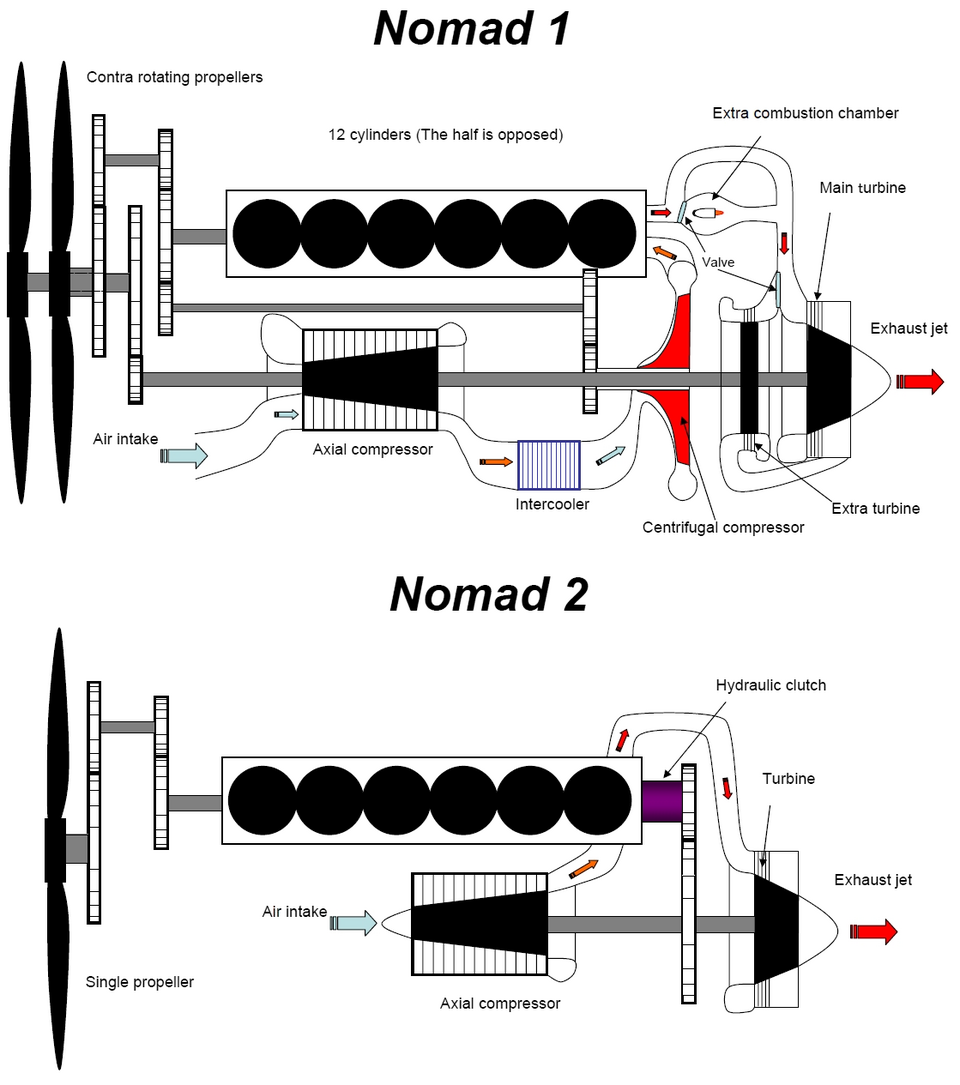

The Nomad was designed to improve fuel efficiency compared to contemporary jet engines, which were less thermally efficient than diesel engines. However, the Nomad was much heavier than a jet engine of the same power, and with the near release of the highly successful Boeing 707 and its engines, it failed to be adopted by any manufacturer. The Nomad program produced two designs: Nomad I and Nomad II.

The Nomad I

Nomad was a 75-liter H-block engine that was highly complex, combining two engines: a turbo-supercharged two-stroke diesel and a turboprop's rotating section based on Napier’s Naiad design. A larger boost was provided by a centrifugal supercharger driven by the engine’s crankshaft. More power was generated by injecting additional fuel into the rear turbine during takeoff, with the injection shut off at cruising speed. The Nomad was tested in the nose of an Avro Lincoln; after more than 1,000 hours of operation, the engine was temperamental but very powerful, producing 3,000 hp and 320 lbf of thrust.

The Nomad II

The Nomad II, successor to the Nomad I, began design before the Nomad I was operational. It featured a simpler design, combining an axial compressor and supercharger, and eliminated the separate centrifuge and intercooler. The engine’s turbine now only powered the compressor, with excess power routed to the main shaft of the Nomad II. This reduced engine size and maintenance by using a single propeller and a mechanical supercharger in addition to a turbocharger. The weight decreased by approximately 1,000 lb (450 kg). An Avro Shackleton, a maritime patrol version of the Lincoln, was used for testing. The Nomad Nm. 7 was planned and announced in 1953 but canceled in April 1955, partly due to the cancellation of the Type 719 Shackleton IV in 1954 and declining interest. Other aircraft considered for the Nomad included the Canadair CP-107 Argus and Bristol Britannia.

Specifications: Napier Nomad II

- Type: 12-cylinder, two-stroke valveless diesel engine compounded w/ three-stage turbine driving both crankshaft and axial compressor

- Bore: 6 in (152 mm)

- Stroke: 7.375 in (187.3 mm)

- Displacement: 2,502 in3 (41.0 L)

- Dry Weight: 3,580 lb (1,620 kg)

- Valvetrain: Piston ported two-stroke

- Supercharger: Napier Naiad turboshaft & gas generator, maximum boost pressure of 89 PSI

- Turbocharger: Engine exhaust gases ducted into Napier Naiad turbine

- Cooling System: Liquid-cooled

- Power Output: 3,150 hp (2,350 kW) max take-off at 89 PSI (610 kPa) boost, not including 320 lbf residual thrust from the turbine at 2,050 rpm (crankshaft) and 18,200 rpm (turbine)

- Compression Ratio: 8.1 (cylinder ratio); 31.5:1 (overall pressure ratio)

- Power-to-Weight Ratio: 0.88 hp/lb (1.45 kW/kg)

The Diesel Engines Of Today

In modern general aviation, diesel engines have made a comeback, driven by three main factors. The first was the 1970s energy crisis, during which Western countries experienced petroleum shortages and higher prices following the Yom Kippur War in 1973 and the Iranian Revolution in 1979. The environmental movement also gained momentum as new scientific research and ecological disasters highlighted the need for nations to adopt more conscious interactions with the planet.

This shift marked key milestones, including the founding of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 and the 1972 UN Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm. Moreover, avgas has always been produced in small quantities, making it a costly, specialized product that's rarely available outside the U.S. compared to cheaper fuels. It doesn’t help that avgas is toxic to humans because of the use of tetraethyl lead; the road use of leaded fuel has been eliminated since the 1990s, and in 2011, researchers estimated that the chemical had caused an annual impact of 1.1 million excess deaths. These factors have led the general aviation community to switch to diesel and biodiesel, which achieve the same goals without the risk of poisoning (or a global ban).

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, diesel engines gained popularity in light aircraft that required less power and aimed to avoid the high costs of avgas. Many modern diesel-powered aviation engines can operate on standard jet fuel or automotive diesel, reducing costs and simplifying logistics. An early key player was the Austrian company Technify Motors GmbH, which developed practical diesel replacements for common 100-350 horsepower piston engines in light aircraft. These innovations led to the Centurion series, first used in the Diamond DA40 Diamond Star (with the Centurion 2.0, delivering 135 hp, or 101 kW). The engines provide better fuel efficiency, and retrofit kits are available for aircraft such as the Piper PA-28 Cherokee and the Cessna 172. Despite Technify’s insolvency in 2008 and the sale of its assets to Continental Motors in July 2013, which halted further development, the company helped pave the way for subsequent advances in diesel aircraft engines.

Many European companies develop and sell diesel engines, including French SMA Engines, Austrian Austro Engines GmbH, Italian DieselJet, and German RED Aircraft GmbH, mostly with 4-6 cylinders and turbochargers. In the U.S., DeltaHawk Engines and Continental Motors are key players; Continental markets Technify’s former Centurion engines as the Continental CD-300. Diesel engines are preferred in UAVs for their fuel efficiency and low maintenance requirements, which enable longer loiter times and lower operating costs, despite noise-related limitations. This makes them suitable for both commercial and military applications. The U.S. Air Force's General Atomics Warrior, an upgraded MQ-1 Predator, uses a Centurion 2.0.

What Is The Future Of Diesel Engines in Aviation?

Due to increased awareness among society and industry of environmental and economic factors, the outlook for diesel engines in aviation appears promising. While diesel engines will never replace jet engines for long-distance international flights, improvements in diesel engine technology and related fields (such as metallurgical and materials sciences), combined with rising costs of specialized avgas, will continue to make them a compelling choice for civilian light aircraft (as evidenced by many European and U.S. manufacturers) and shorter-range carriers operating coast-to-coast routes.

Additionally, the rise in UAV research, development, and manufacturing creates another market for lightweight, affordable diesel engines. This is especially important for military operations, which require long loiter times, easy maintenance, and low operating costs to be effective. Advances in the military sector often influence the civilian sector (for example, the U.S. military’s ARPANet of the 1960s, which introduced several innovations that laid the groundwork for the modern internet). However, the outcomes of these innovations and advancements remain uncertain, and they may not reach widespread civilian use for years, as companies often use military contracts to fund tooling and development of civilian versions to justify the costs. It’s also becoming more likely that diesels will adopt a hybrid model as alternative fuels become more attractive and affordable.